Experimental Desing and Acquisition Optimization

As an engineer entering the world of neuroscience, I initially struggled with the uncertainty and high levels of noise inherent in neuroscience research—particularly in fucntional MRI (fMRI). Early on, I decided to dedicate part of my time to better understanding the properties of the signals measured with BOLD fMRI, studying their reliability, and optimizing scanning parameters. Some of these studies are highlighted below.

Exploring the Quality of fMRI Data

Exploring the Quality of fMRI Data

One important aspect of scientific data is its reliability. That said, perfect test–retest reliability is neither expected nor necessarily desirable when studying a dynamic system like the human brain, which naturally changes from one measurement to the next. The real challenge lies in distinguishing genuine physiological variability from non-physiological noise and other confounding sources. Over the years, I have investigated the reliability of both task-based and resting-state data across multiple projects—two of which are highlighted here.

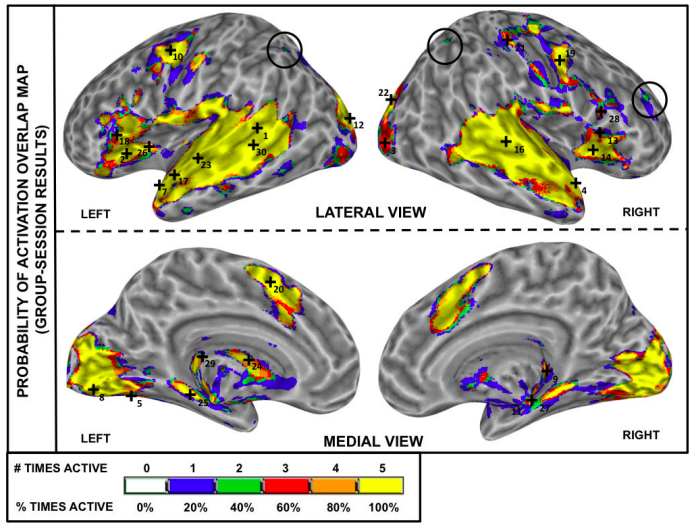

My first exploration of task-based fMRI reproducibility is summarized in one of my PhD thesis publications. In that study, I evaluated the test–retest reliability of an auditory sentence comprehension task. This topic was of particular interest to my host lab, which investigated, among other things, the neural correlates of speech comprehension in cochlear implant users. Through this project, I was introduced to the field of quality assurance, learned multiple methods for assessing test–retest reliability (e.g., Dice coefficient, intra-class correlation coefficient), and gained deeper insight into one of fMRI’s main interpretational challenges: correctly identifying sources of individual differences that persist despite high group-level reproducibility. Our findings showed that the proposed task performed well at the group level, suggesting it could serve as a reliable protocol for future population-level studies (see one example here).

Another deep dive into reproducibility came from a study examining how [patterns of resting state functional connectivity](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intraclass_correlation) (rs-fMRI FC) evolve during a one-hour scan. Unlike task-based fMRI, rs-fMRI scans require little from participants—simply to stay still, remain awake, and let their minds wander. This simplicity makes the approach ideal for clinical populations and easier to acquire than task-based data.

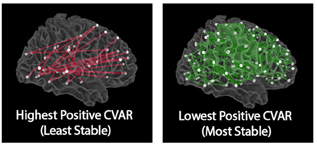

By the time I entered this area, it was well established that rs-fMRI FC, averaged over several minutes, is reliable across sessions and carries meaningful phenotypic information (e.g., traits, symptoms). Yet, emerging evidence suggested these connectivity patterns fluctuate substantially within a single scan—raising a fundamental question: is this variability meaningful or merely noise?

In this first exploration of time-varying FC, I focused on two key questions: (1) how scan duration affects the reliability of average connectivity estimates, and (2) whether the observed variability exhibits meaningful spatial structure. The first question is practical—fMRI is expensive, and participants can only remain still for so long—while the second probes whether the variability reflects genuine neural dynamics.

Our results showed that reliability improves with scan length, with at least 10 minutes of data needed for stable estimates. We also identified distinct spatial patterns: the most stable connections were interhemispheric links between homologous regions, while the most variable involved cross-network, non-homologous connections in frontal and occipital cortex—regions supporting higher-order cognition.

Selected Publications on Data Quality and Reliability:

- Gonzalez-Castillo J and Talavage TM “Reproducibility of fMRI activations associated with auditory sentence comprehension”. NeuroImage (2011)

- Gonzalez-Castillo J et al. “The spatial structure of resting state connectivity stability on the scale of minutes”. Frontiers in Neuroscience (2014)

- Gonzalez-Castillo J et al. “Variace decomposition for single-subject task-based fMRI activity estimates across many sessions” NeuroImage (2017)

- Handwerker DA et al. “The continuing challenge of understanding and modeling heodynamic variation in fMRI” NeuroImage (2012)

- Soltysik DA et al. “Head-repositioning does not reduce the reproducibility of fMRI activation in a block-design motor task” NeuroImage (2011)

Optimization of Acquisition Parameters for fMRI

Optimization of Acquisition Parameters for fMRI

Setting up an fMRI acquisition protocol involves making a large number of decisions. Some are fairly straightforward, such as selecting the scanner field strength and pulse sequence—often constrained by what is available at a given imaging center. The same applies to parameters tied directly to experimental design, such as temporal resolution, spatial resolution, and spatial coverage. However, many other parameters—those more closely related to the physics of MRI signal acquisition, such as echo time, flip angle, or bandwidth—are often treated as less critical and left at their “default” values. News alert: that assumption is not true. These parameters, though sometimes overlooked by non-physicists, can have a substantial impact on data quality.

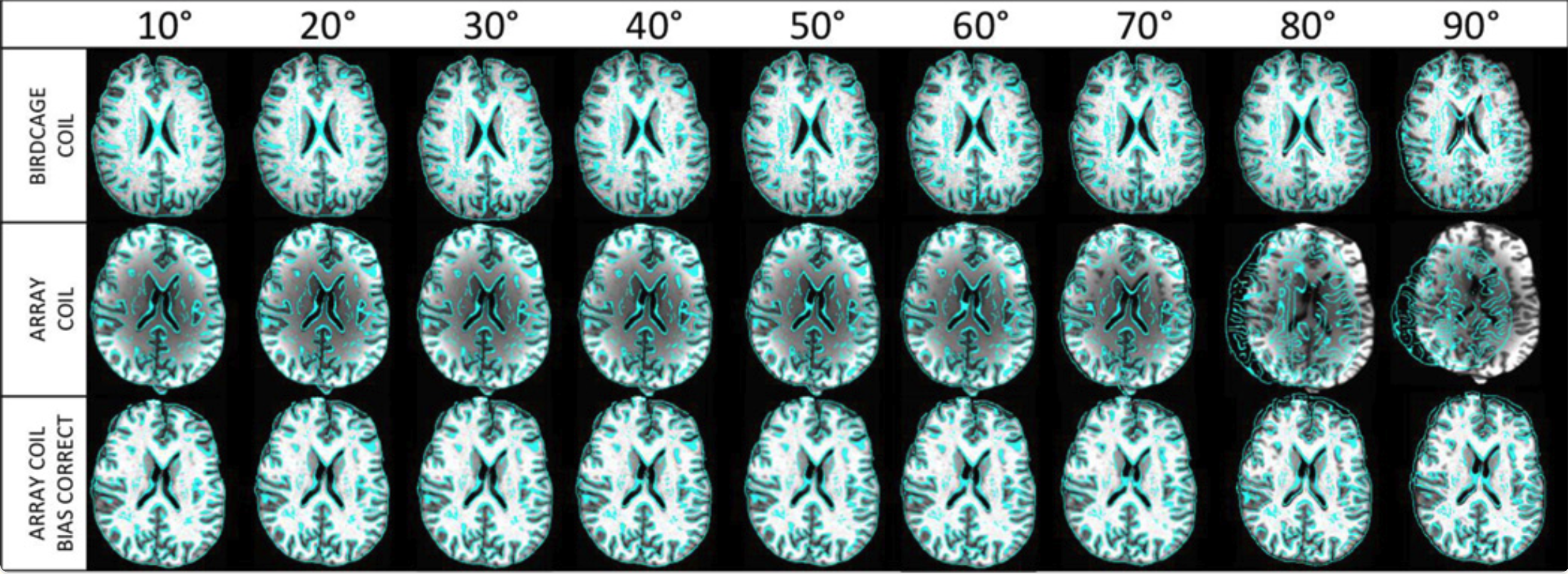

One particularly important parameter is the imaging flip angle (FA), which defines the amount of rotation (or “flip”) applied to the net magnetization vector by the radiofrequency pulse preceding signal readout. It is common practice to set the flip angle to the Ernst angle for gray matter, under the assumption that this choice maximizes sensitivity in that tissue compartment—typically the main focus of fMRI studies. Although this approach has its advantages, the Ernst angle is only truly optimal when data are dominated by thermal (non-physiological) noise. In our work, we developed a new theoretical model demonstrating that, under conditions where physiological noise dominates, the optimal flip angle can in fact be substantially lower without compromising sensitivity to neural activity.

The figure above, taken from our publication, illustrates the key finding from our empirical validation of the model. Even when the flip angle was reduced to as low as 9° (compared to an Ernst angle of 77° for this case), the percent signal change and spatial activation profiles in the visual and motor cortices remained stable. In other words, we were able to detect these regions of activity with comparable sensitivity—despite lowering the flip angle by nearly an order of magnitude.

Why does this matter? Using low flip angles offers several important benefits: reduced energy deposition in tissue (less RF power), decreased sensitivity to inflow, through-plane motion, and physiological noise (all notorious sources of confounds in fMRI), and improved tissue contrast. The latter, as we demonstrated in a follow-up study (main figure reproduced below), can markedly enhance the quality of functional-to-anatomical registration.

In the figure above, skull-stripped anatomical scans serve as the underlay, with functional data contours overlaid after spatial registration. Across all coil configurations (rows), alignment performs best at lower flip angles but deteriorates at or above the Ernst angle—especially when no correction for intensity inhomogeneity is applied. In essence, this figure illustrates how a theoretical insight (that lowering flip angles preserves sensitivity to neural activation) directly translates into a practical advantage: improved alignment between functional and anatomical scans.

Selected Publications on Optimization of fMRI Acquisitions:

Gonzalez-Castillo et al. “Physiological noise effects on the flip angle selection in BOLD fMRI” NeuroImage (2011)

Gonzalez-Castillo et al. “Effects of image contrast on functional MRI image registration” NeuroImage (2013)

Talavage TM, Gonzalez-Castillo et al. “Auditory Neuroimaging with fMRI and PET” Hearing Research (2014)

Hu S, Olulade O, Gonzalez-Castillo J et al. “Modeling hemodynamic responses in auditory cortex at 1.5T using variable duration imaging acoustic noise” NeuroImage (2010)

Realtime fMRI

Realtime fMRI

This topic is close to my heart for two reasons. First, I believe that real-time fMRI opens the door to interactive experimental protocols that may hold the key to novel therapeutic interventions (via fMRI-based neurofeedback) and, ultimately, to a deeper understanding of how self-driven consciousness relates to systems-level brain activity and connectivity patterns. Second—and on a more personal note—real-time fMRI is what first brought me to the NIMH as a summer student. Those summers set in motion the path that has since become nearly two decades of work at the NIMH. More importantly, they gave me the privilege of working closely with the late Dr. Jerzy Bodurka, an extraordinary scientist who spent countless hours teaching me the principles of MRI physics and data acquisition.

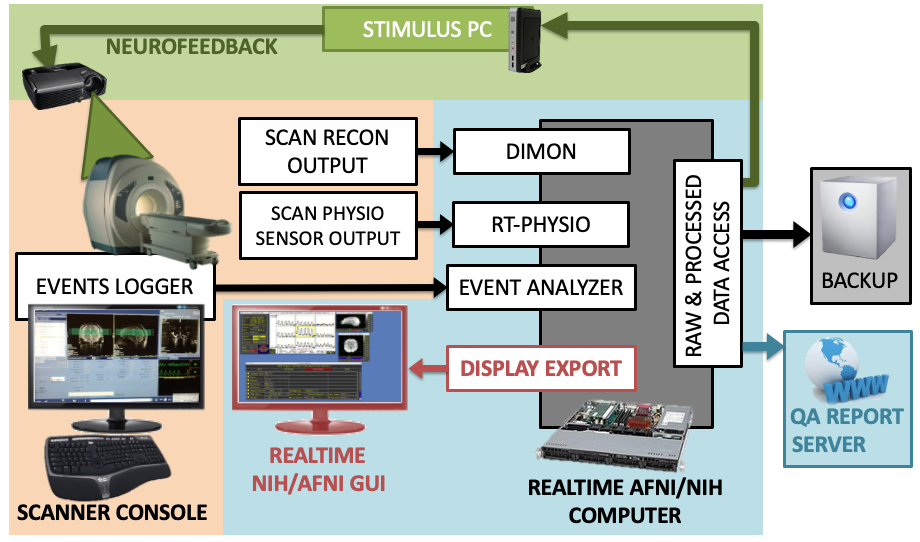

The work I carried out during those two summers did not result in any publications, as I devoted both opportunities to developing new functionalities for the real-time fMRI systems running on GE scanners at the NIH Functional Imaging Facility. During my first summer, I developed C code to synchronize the recording of respiratory and cardiac traces with concurrent fMRI acquisitions. In the second, I created a basic neurofeedback GUI that was later used in several pilot studies. While the first functionality remains in use to this day, the second was eventually superseded by a newer version developed by Dr. Vinai Roopchansing.

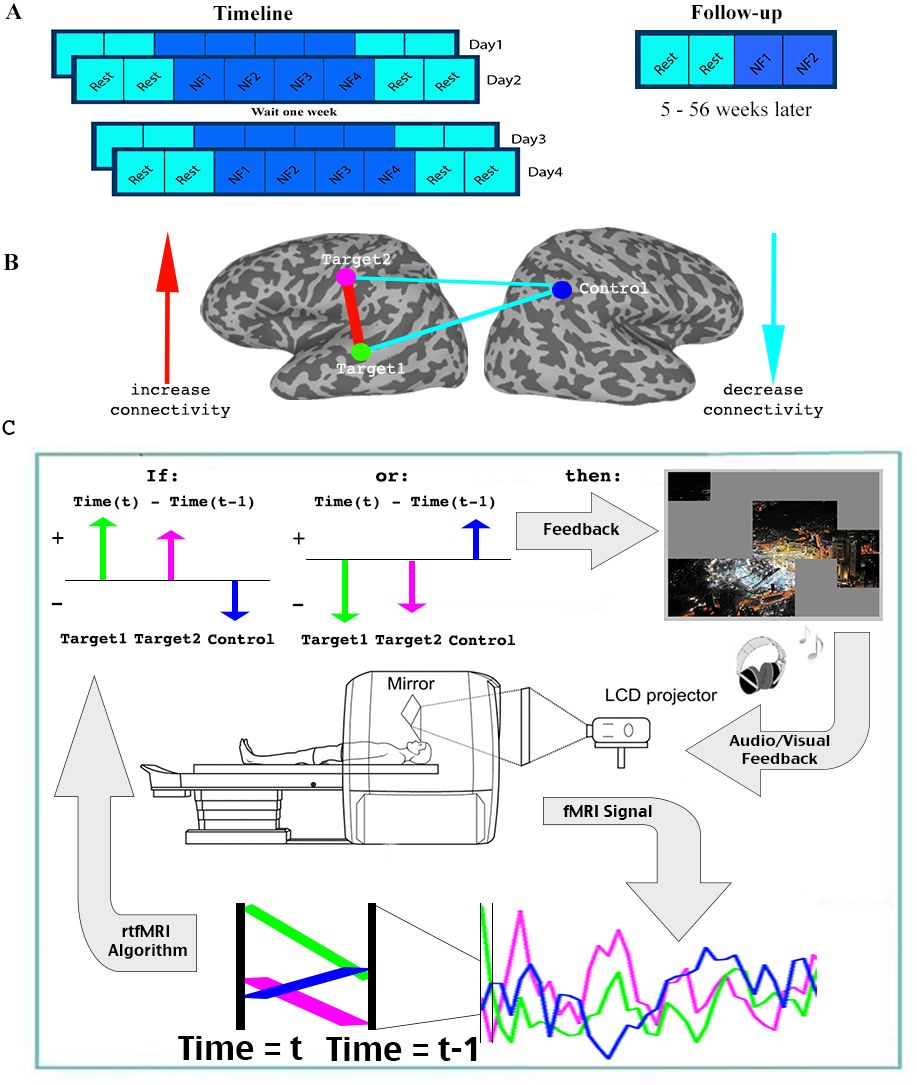

But don’t be fooled—that was not the end of my dive into real-time fMRI. Over the years, I have been fortunate to collaborate with many NIH researchers in designing, developing, and interpreting neurofeedback experiments. Of particular note is my collaboration with Dr. Michal Ramot on the use of covert fMRI neurofeedback to alleviate social symptoms associated with autism spectrum disorder, as well as our subsequent methodological work improving upon the approaches used in that seminal study. Please see the Clinical Research section for more details.

Today, I am working on the development of a new real-time fMRI software suite, (rtcog), designed to monitor patterns of neural activity as scanning unfolds—and to trigger experimental interventions whenever a target pattern emerges. This framework has broad applications for the scientific study of spontaneous neural processes, a key focus of my current research.

For example, certain brain regions such as the visual cortex often activate spontaneously during resting-state scans, even in the absence of visual stimulation (e.g., while subjects fixate on a crosshair). Why does this happen? Could these activations reflect conscious processes such as visual imagery or internal inspection of one’s surroundings? Or are they driven by purely unconscious dynamics? We don’t yet know. But by continuously tracking participants’ brain activity in real time—and triggering brief self-report probes immediately after spontaneous activation events—we may begin to answer these questions. The real-time software I am now developing in collaboration with colleagues at the NIH will make this type of experiment possible.

Publications on Realtime fMRI:

Gonzalez-Castillo J et al. “Editorial: Towards Expanded Utility of Real Time fMRI Neurofeedback in Clinical Applications” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience (2020)

Ramot M and Gonzalez-Castillo J. “A framework for offline evaluation and optimization of real-time algorithms for use in neurofeedback, demonstrated on an instantaneous proxy for correlations” NeuroImage (2019)

Ramot M et al. “Direct Modulation of Aberrant Brain Network Connectivity Through Real-Time Neurofeedback” eLife (2017)