Research

What are the neuronal drivers of time-varying functional connectivity?

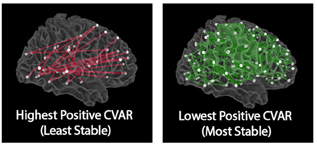

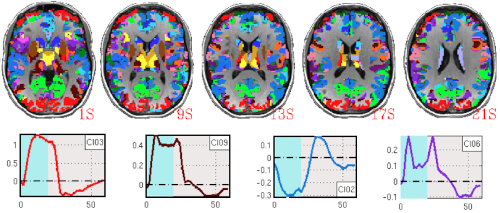

Functional connectivity, as measured with BOLD fMRI, exhibits dynamic behavior at the scale of seconds, with rich spatiotemporal structure both during resting state and task scans. What does such dynamicity reflects? To what extent do aberrant patterns of time-varying functional connectivity signal pathology? Those are all open questions. In early studies, we focused on characterizing the sptio-tempotal structure of this dynamic phenomena during the resting state. We were able to show that most stable connections correspond primarily to inter-hemispheric connections between left/right homologous regions; while most variable connections correspond to inter-hemispheric, across-network connections between non-homologous regions in occipital and frontal cortex (e.g., those subserving higher-order cognitive functions). We also demonstrated that well established resting state networks disintegrate on many occasions during a single scan, questioning the interpretability of such networks.

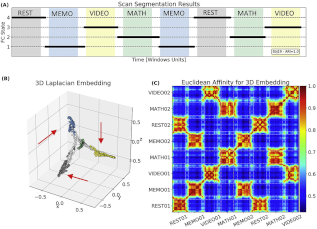

In addition to studying the region-to-region spatiotemporal structure of time-varying functional connectivity during resting state, I have also conducted experiments aimed at validating the interpretability of whole-brain dynamic functional connectivity patterns as markers of on-going cognition. In particular, using multi-task scans and unsupervised machine learning we demonstrated a direct link between short-term (tens of seconds long) whole-brain functional connectivity patterns and on-going mental processing at the single-subject level. More recenlty, we have applied the same methodology to resting-state data and demonstrated that it is possible to infer the cognitive nature of a subjects’ mental activity at discrete scan segments on the basis of time-varying connectivity and hemodynamic deconvolution.

References:

- Gonzalez-Castillo J et al. “Imaging the spontaneous flow of thought: distinct periods of cognition contribute to dynamic functional connectivity during rest”. NeuroImage (2019)

- Gonzalez-Castillo J et al. “Tracking ongoing cognition in individuals using brief, whole-brain functional connectivity patterns”. PNAS (2015)

- Gonzalez-Castillo J, Bandettini PA “Task-based dynamic functional connectivity: recent findings and open questions”. NeuroImage (2018)

- Gonzalez-Castillo J et al. “The spatial structure of resting state connectivity stability on the scale of minutes”. Frontiers in Neuroscience (2014)

What are the neuronal correlates of self-driven thoughts and inner experiences?

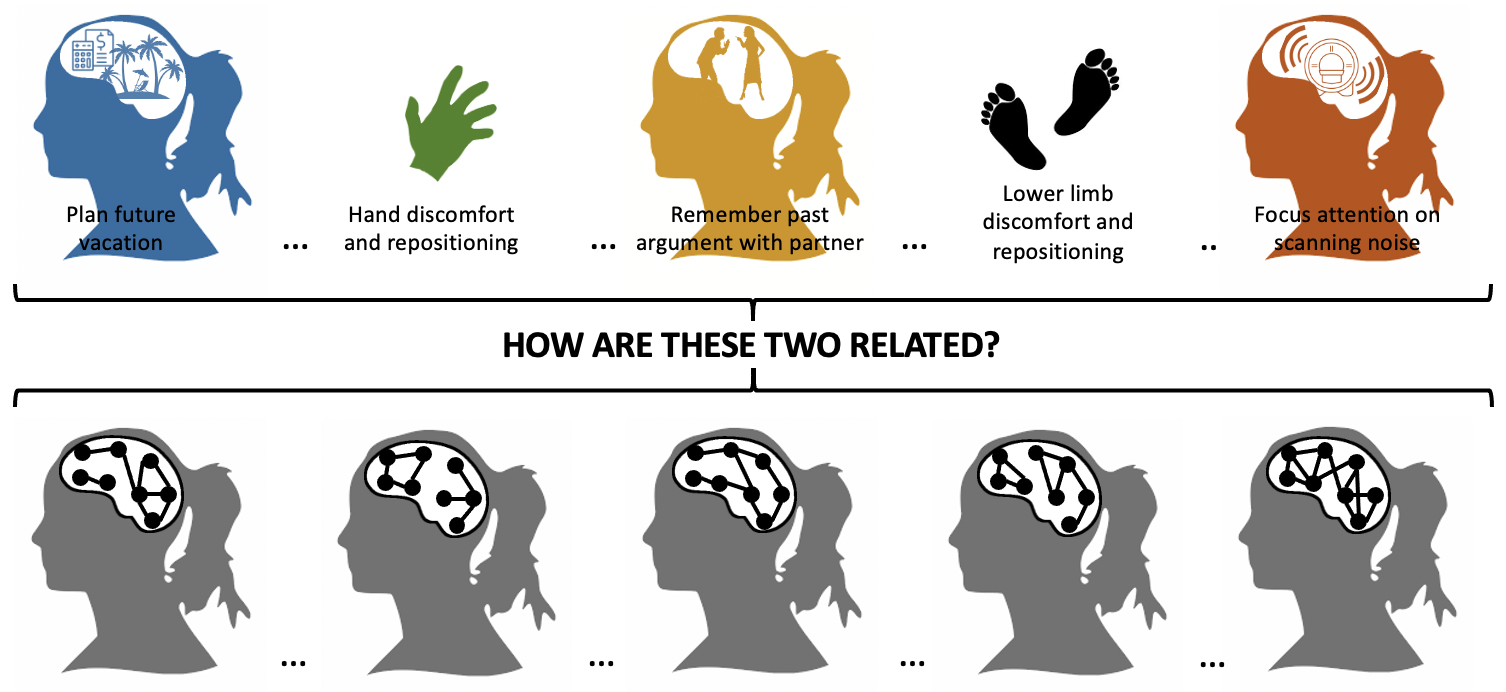

Brain activity is not always linked to concurrent external environmental demands or stimuli. In fact, complex dynamical patterns of activity—-and their conscious manifestation as an incessant stream of thoughts, emotions and sensations—-constantly unfold in otherwise apparently idle individuals. Despite their ubiquity and core role for survival, the neurobiological correlates of such inner experiences remain largely unknown. This scientific gap is mostly due to how difficult is to objectively characterize something that is so inherently covert and personal. Nonetheless, recent developments in functional neuroimaging, idiographic/experiential science and artificial intelligence (AI) provide a unique opportunity to build scientific models of the neurobiological, behavioral and clinical correlates of free thought. We are currently in the process of conducting new experiments that combine real-time fMRI, experiential methods and machine learning to learn more about the neural correlates of free thought.

References:

- Gonzalez-Castillo J et al. “How to interpret resting-state fMRI: ask your participants” Journal of Neuroscience (2021)

What is the true extent of neural activity as measured with fMRI?

The majority of task-based fMRI studies focus exclusively on interpreting positive BOLD deflections that tightly follow external stimuli or task demands (i.e., those sustained as long as the experimental intervention is in place). Although exclusive focus on positively sustained BOLD responses have proven successful to uncover the neuronal correlates of a myriad of human behaviors; unfortunately, this practice results in true neuronal responses continuously passing undetected in fMRI. As such, current conceptualizations of brain function based on task-based fMRI research are incomplete.

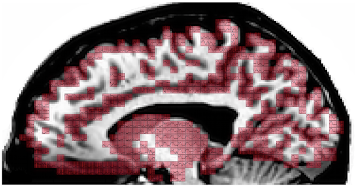

In the past, we have shown how non-conventional BOLD responses, namely negative signal deflections accompanying task performance (negative sustained BOLD) and phasic responses that occur at the onset/offset of experimental events, can be modulated by cognitive demands. Using data with approximately six times higher signal-to-noise ratio than conventional fMRI, we were able to demonstrate that BOLD signal changes correlated with experimental task-timing occur in over 95% of the brain even for the simplest of tasks. These results not only highlight the inadequacy of current dichotomical interpretational models (active/inactive), but also challenge long accepted localizationist views of brain function demonstrating how non-canonical responses ought to be discussed if one is to acquire a full understanding of brain function. Important questions remain such as how to differentiate essential (i.e., signaling regions that are indispensable to accomplish a given task) from accessory activations, or how to report and interpret whole-brain activity maps.

References:

- Gonzalez-Castillo J et al. “Whole-brain, time-locked activation with simple tasks revealed using massive averaging and model-free analysis”. PNAS (2012)

- Gonzalez-Castillo J et al. “Task Dependence, Tissue Specificity, and Spatial Distribution of Widespread Activations in Large Single-Subject Functional MRI Datasets at 7T”. Cereb Cortex (2015)

How can we improve the quality of fMRI data?

Signal fluctuations of no neuronal origin (i.e., noise) account for well over 75% of the variance in fMRI data. In fact, excessive noise is one primary cause of low reliability and low sensitivity in fMRI. To minimize the detrimental effects of elevated noise levels, complex pre-processing always precedes statistical analyses. Yet, current pre-processing algorithms are flawed, and superior, multipurpose techniques that can remove non-neuronal variance with minimal human intervention are in great demand. This is particularly true for clinical fMRI, where merging data across subjects is not possible, and manual intervention must be minimized to optimize clinical usability.

One way to improve the quality of fMRI data is to appropriately tune scanning parameters during acquisition. One such parameter is the imaging flip angle, which affects signal levels, tissue contrast and the ratio between thermal and physiological noise. In the past, when acquiring fMRI data, the flip angle was often set to the Ernst angle to maximize spatial signal-to-noise ratio. This is a logical choice for anatomical imaging, but not necessarily for fMRI where temporal signal fluctuations are the target variable. Using a combination of simulations and empirical data, we were able to demonstrate that one can choose flip angles well below the Ernst angle when physiological noise (e.g., cardiac and respiratory fluctuations) is the dominant noise source in fMRI recordings. Based on these results, we defined strategies to compute optimal flip angles for fMRI studies. These results constitute an important improvement for how to acquire fMRI data, as reductions in flip angle automatically translate into reduction of RF power, limitation of apparent T1-related inflow effects, reduction of through-plane motion artifacts, lower levels of physiological noise, and improved tissue contrast.

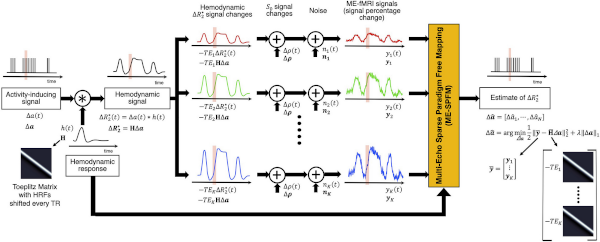

In recent years, several groups have turned their attention to multi-echo (ME) fMRI as a technique that can help recover signal in regions characterized by large dropout and that permits automatic removal of most common noise sources in fMRI. At the Section of Functional Imaging Methods, my research home, I have actively contributed to the design and evaluation of ME denoising algorithms that rely on independent component analysis to detect spatially independent signals present in the data. Those are subsequently classified into “good” or “bad” on the basis of how they change in amplitude across the different echoes. Detailed information of how this ME denoising method works can be found on the tedana site. In parallel, and in collaboration with Dr. Caballero-Gaudes at the Basque Center on Cognition, Brain and Language, I have worked on re-formulating hemodynamic deconvolution methods to take advantage of the extra information available in ME data. In a recent study, we showed how a novel ME formulation significantly outperforms its single-echo counterpart. An implementation of our ME deconvolution method (3dMEPFM) is currently distributed with AFNI.

References:

- Caballero-Gaudes C, Moia S, Panwar PA, Bandettini PA, Gonzalez-Castillo J. “A deconvolution algorithm for multi-echo functional MRI: multi-echo sparse paradigm free mapping” NeuroImage (2019)

- Ramot M, Gonzalez-Castillo J. “A framework for offline evaluation and optimization of real-time algorithms for use in neurofeedback, demonstrated on an instantaneous proxy for correlations” NeuroImage (2019)

- Gonzalez-Castillo J, et al. “Evaluation of Multi-Echo ICA denoising for task based fMRI studies: block designs, rapid event-related designs, and cardiac-gated fMRI” NeuroImage (2016)

- Gonzalez-Castillo J et al. “Physiological noise effects on the flip angle selection in BOLD fMRI” NeuroImage (2011)